About

500 years ago, in the twilight of the period we call the Renaissance, there

began to appear near the coast of the Northern Adriatic around the present

city of Venice, Italy, a group of country houses unlike any homes ever seen

before. They were all within a radius of about 50 miles, and they were all

the work of a single architect.

Toward

the end of his career, that architect used the new technology of movable

type -- then about 100 years old -- to produce a four-volume illustrated

catalog of his work with a commentary on his principles and methods. The

book, entitled The Four Books of Architecture, stunned the European

world. It revolutionized Western architecture of the 17th and 18th centuries;

it produced the school of Southern architecture in the 19th century; and

it remains a major influence throughout the world even today.

Andrea

Palladio's personal history would seem beyond the imagination of even

Horatio Alger. Beginning as a 13-year-old apprentice to a stonemason,

he grew up to become the sought-after companion of aristocrats and intelligentsia,

as well as the political, military and business leaders, of his day --

the dominant figure in his field, not just in his own lifetime, not just

in the lifetime of those who knew him, but now -- more than 400 years

later.

What

can explain this? It seems to me that there's only one possible explanation,

namely, that he did just what he set out to do: From his studies of the

past and his analysis of contemporary needs, he did in fact distill timeless

and universal principles.

Palladio's

Contemporary Needs

Let

us begin by looking at the needs of his time. In Palladio's time Venice

was not just a city. It was the center of a vast empire with military

and commercial enclaves all around the Adriatic and Eastern Mediterranean.

In fact, at its height, Venice was one of the greatest military and commercial

powers on earth. In population, four times the size of Rome and London

combined.

Venice's

power came from the fact that its forces stood astride both of the great

East-West trade routes of the day: the Northern or land route to Asia

and the Orient, and the Southern or sea route.

Venice

rose to power in the 1100s by developing an advanced system for constructing

war galleys. In fact, Venice originally was entirely a sea power. Based

on a group of small islands in an Adriatic lagoon several miles from the

mainland, the mighty Venice had no land at all on the Italian mainland

until the mid 1300s. Military expansion on the Italian mainland then continued

until the early 1500s. By then three dramatic events had set in motion

a land rush for the vast undeveloped areas of the European mainland west

of Venice.

First,

the Ottoman Turks, who had for decades been nibbling away at Venezia's

eastern outposts, in 1453 stormed and captured Constantinople, the great

Christian city of the eastern world, the massive capital of the long-faded

Eastern Roman Empire. This and related developments effectively clipped

Venice's already withered control of the land route to Asia, and put its

sea route under great pressure as well.

Second,

in 1492 the Spanish expedition of Christopher Columbus discovered the

Western world, which in ensuing years rapidly replaced the Orient as the

most lucrative destination of European traders.

Third

and finally, in 1497 Vasco da Gama of Portugal demonstrated a new sea

route to Asia by sailing around the southern tip of Africa and across

the Indian Ocean. Now the merchants of Western Europe no longer had to

pay Venice for safe passage to the East. In just 44 years the Mediterranean

Sea -- Medi-Terrano, the center of the earth for thousands of years --

went from being the center of the earth to the center of very little.

Fortunately,

after hundreds of years of fighting, peace had broken out on the mainland.

The mainland areas near Venice finally had the security necessary for

large-scale agriculture and for transporting those harvests to the population

centers.

There

was also a new crop to plant -- corn from the New World. (Remember that

Columbus' voyage -- that crippling event for Venice -- was a current event,

only about 50 years earlier.)

At

the same time, to pull these elements together, there was a class of entrepreneurs

with the capital to clear the fields, drain the swamps, organize the farm

centers. These were the noble families of Venice. They had amassed their

fortunes in foreign trade, in shipping, and -- surprisingly for a sea-going

class -- in agriculture: Huge plantations in Crete, in Cyprus, and elsewhere

through their overseas empire. Now they could put their capital and their

overseas agricultural experience to work close to home.

It

being a constant trait of mankind to make a virtue of necessity, these

nobles also concluded that getting away from the hurly-burly and commerce

of the city, getting closer to the calm and reflection of country life,

was beneficial to the spirit, the virtuous, ennobling thing to do. Listen

to Palladio himself:

"[B]y

exercise, which one can take in the country on foot or on horseback, they

will preserve their health and their strength, and there finally their

spirits, tired of the agitation of the city, will take great refreshment

and consolation, and they can attend quietly to the study of letters,

and contemplation -- as for that purpose the wise men of old times used

often to follow the practice of retiring to similar places, where they

were visited by good-hearted friends, and their kin . . . ."

The

Villa Problem

But

where were these noble families to stay in the countryside? Mud huts wouldn't

suit. They needed a magnificent home, something that reflected their own

magnificence and virtue. But it wouldn't do just to build a Venetian palace

out here in the countryside. That sort of building wouldn't be functional

-- suited to the business of supervising a large agricultural establishment,

or storing the grain and wine produced. That kind of urban building wouldn't

facilitate the communication with nature that the man of virtue requires

for repose and contemplation. And perhaps most important, that kind of

building would cost an arm and a leg.

Something

entirely new was needed. Something magnificent, but inexpensive. Something

comfortable, restful, yet at the same time functional as the center of

activity for dozens of farm workers. Fortunately, a certain stone mason

in Vicenza -- about 60 kilometers from Venice -- was waiting with the

answer. Moreover, it turned out that the problem posed was not unique

to Venice. It turned out to be the central problem at the intersection

of modern architecture and modern economics. Therefore, Andrea Palladio's

solution has been the cornerstone of architecture ever since.

Remember

the problem: The need for a structure that is magnificent, yet inexpensive;

comfortable, yet functional.

Palladio's

3-Part Solution

Drawing

upon his own insights and observations, upon the re-discovered treatise

of the Roman writer Vitruvius and the writings of Alberti and Serlio,

and (to a lesser degree) upon the works of elders such as Raphael, Falconetto,

Sanmicheli and Sansovino, Palladio's devised a solution with three principal

elements:

- Dramatic

exterior motifs.

- Economical

materials.

- Internal

harmony and balance.

Dramatic

Exterior Motifs

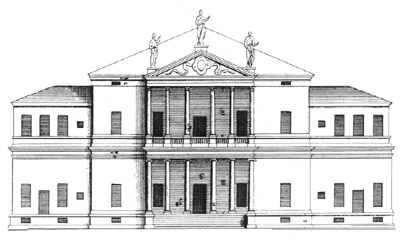

Palladio

ultimately developed three primary types of exterior elevation that we

have come to characterize as Palladian. The simplest, most modest and

most numerous among the constructed works, Type I (as I will call it),

presents a loggia pierced by three openings.

The

second, Type II, borrows the Greek temple front. Palladio never saw the

Greek monuments, but he visited Rome five times. A long and dangerous

journey. There he saw, mostly in ruins, the classic public buildings of

Imperial Rome -- which the Romans, of course, had borrowed from the Greeks.

It was Palladio's inspiration to adapt the Greek pediment and columns

to private residences -- an audacious step, and one that could only be

taken by a confident architect with proud patrons.

Finally,

the third and most innovative and modern of the three motifs: the double-columned

loggia. That is, complete columns above and below.

The

first motif, the three-opening loggia, appears in Palladio's very first

villa: Villa Godi, which was constructed about

1540. There is a certain clumsiness to this first outing. Heavy volumes

at the left and right are reminiscent of the fortress-like villas of the

prior century and the early 1500s. Villa Trissino, the villa in Cricoli

that Palladio's great benefactor Giangiorgio Trissino built two or three

years earlier, comes to mind. There's really nothing here to inspire the

architects of future centuries. At least there's nothing obvious. But

I would suggest that there are a few elements here that you should begin

to watch -- elements that you will see evolve and mature.

First,

there is symmetrical balance from left to right. This may seem a small

thing -- and it certainly has many antecedents -- but I would remind you

that it is a striking contrast to the unsymmetrical gothic palaces of

Venice. And it becomes a cornerstone of Palladian villas.

Secondly,

the three-opening loggia -- certainly not a new idea either -- has been

combined with other elements in a way that begins to open the villa to

the world outside. Lasting peace -- at least in a relative sense -- had

come to the Veneto. The great, devastating War of the League of Cambrai

-- was now 30 years in the past. That fact is subtly underscored by Villa

Godi.

Let's

consider a few more examples of this triple-opening loggia. There's less

variety among these than we find in the grander villas of the second and

third motifs, although he sometimes elaborated the three openings with

a Serliana motif. Villa Pisani at Bagnolo (probably incorporating an earlier

tower on the left), Villa Caldogno, Villa Saraceno, Villa Gazzotti --

are all substantially similar, and modest in their exterior motif. But

a comparison of Villa Saraceno, for example,

and Villa Gazzotti shows a fascinating element beginning to emerge at

Villa Gazzotti: the pillars of the loggia begin to metamorphose toward

classical columns supporting a pediment! At Villa Gazzotti the "columns"

are only pilasters, but clearly a pediment of the Greek style is beginning

to emerge atop a traditional Italian motif. Not yet the dramatic classical

adaptation found in Palladio's great works, but a suggestion of the future.

The

story turns dramatically when we move to the true temple-front examples.

Now we are moving to the great homes in the history of architecture. At

Villa Barbaro in Maser we see one of Palladio's

most magnificent and influential designs. Influential in a whole range

of ways. First, we see the true Greek temple-front. Not projecting forward

in this example, but surmounted by a brilliant classical pediment. What

chutzpah!

This

is the design for the front of a temple. Palladio and the proud patricians

of Venice have had the self-confidence to put it on the residence of a

mere mortal. Of course, to keep things in perspective, the temple/villa

is flanked by adjoining farm buildings for storing grain and wine and

for housing farm animals. The Venetians call these farm buildings "barchessas."

At

the ends of the barchessas Palladio added dovecotes on top and faced them

with sundials. The result is one of the lasting legacies of Western public

architecture: the so-called 5-part profile.

Count

the parts from left to right: 1-Left Dovecote; 2-Left Barchessa; 3-Residence;

4-Right Barchessa; 5-Right Dovecote. How many buildings have you seen

based on this scheme? Start with the U. S. Capitol building. But in England

there are dozens of country homes with this 5-part profile. Even American

ranch-style homes frequently display this Palladian profile. Now you know

where it began.

Here's

another example of the 5-part form: Villa Emo at

Fanzolo. The dovecotes on the ends are less prominent here, but look at

the temple front. Now the columns are free-standing.

Where

could this evolution go next? Palladio moved ahead to his third major

motif. Not one loggia, but two loggias, one on top of the other. The garden

side at Villa Cornaro shows this motif in its

simpler form, with the loggia recessed within the central core of the

villa. It's a place to sit and look from a protected area out into the

world. But Villa Cornaro is one of Palladio's double-faced villas, and

the street side brings the grand culmination of the evolution of Palladio's

exterior motifs.

It's

the leap to the modern world! Suddenly the

"rooms" are not buried in the core and looking out at the world. Now the

rooms are thrust out into the midst of the world! What a break with the

past! The first appearance in architecture of projecting double-columned

loggias with architrave and pediment.

Think

how far things have come. Compare this bold villa-as-part-of-the-world

with the glum defensive Villa Godi with which Palladio began.

This

must be one of Palladio's greatest achievements. Perhaps he was inspired

in some way by Villa Giustinian about 40 miles away in Roncade. But essentially

we have here a most unusual event: a completely new idea. Here is the

first example of this motif ever built. Hard to believe, because now it

seems so common. I think of it as being like the invention of calculus.

A device to be used throughout posterity.

Economical

Materials

So

much for Part I of Palladio's solution: the dramatic exterior motifs.

Part II of the solution, you will recall, was the use of economical materials.

As

you know, the palaces of Venice itself are built of stone brought from

distant mainland quarries. The stone was then usually clad in marble from

Istria or beyond. But because Palladio had achieved his visual impact

through his design motifs, he could build his villas of brick instead

of stone, and clad them in stucco instead of marble. Surprised? Yes, you

probably thought these magnificent villas we've been seeing were built

of granite. But now you know their nasty secret: brick. Brick and stucco.

Even

the ornate capitals hold a secret: terra cotta. At least on the sunny

south side; on the north facade the capitals might be stone because of

the weather. Terra cotta! Can you believe those capitals

are like 450-year-old flower pots? The architraves supporting these mighty

pediments? Wood! Wood covered with straw lathing and then stucco.

Now

let's move inside. If you've visited inside any of the palaces of Venice

itself, you may have noticed that the walls are bare although the cornices

and ceilings may be magnificently decorated. The missing element today

is the tapestries. In the 16th century the palace walls were covered in

magnificent tapestries -- both for their beauty and for their insulating

qualities in the winter.

Now,

since the villas out in the countryside were only for use in the summer

farming season, the insulating qualities were not needed for warmth. So,

if the walls could be decorated some other way, the huge cost of tapestries

could be eliminated entirely. Frescos were the answer. Did you ever for a minute imagine

that the magnificent frescos of the villas were a cost-cutting device?

If you didn't mind going down-market, you could hire Veronese or Zelotti

to stop by for a month or two and give you some imitation tapestries and

columns and statues.

In

fact, only the Cornaro family -- the richest family of the Republic --

seems to have resisted the temptation; their villa at Piombino held out

for the real thing: real columns, real niches,

real statues -- not cheap imitations by Veronese.

Interior

Harmony and Balance

This

brings me to the last, the least understood, and the most evanescent element

of Palladio's solution: Palladio's interior harmony and balance.

It's

the difference between Palladio himself and Palladianism. His exterior

motifs -- innovative as they are -- can be copied. His economical materials

can be duplicated, even improved. (Thank God Palladio didn't know about

styrofoam!) But Palladio's balance and harmony seem to live only in his

18 surviving villas of the Veneto. The harmony and balance of Palladio's

interior spaces is their great epiphanal triumph -- but it seems to elude

the Palladians of other countries and later times. Palladio certainly

tried to conceptualize and convey his insight. But perhaps it's like analyzing

the success of the Mona Lisa in order to duplicate its effect in another

painting.

First,

and fundamentally, Palladio states that the parts of a house must correspond

to the whole and to each other. This seems simple in theory but has proved

nearly impossible for most of posterity's Palladio wannabes. Standing

in one of Palladio's villas -- and I mean standing anywhere in it -- you

have at all times a sense of where you are within the total structure.

To use a currently fashionable term, the concept of the floor plan is

transparent. Compare that with a large modern house where you never know

what twist or turn or size or shape of room may lie around the next corner.

Secondly,

Palladio varies the volumetric size of his rooms with the creativity and

discipline of a Bach fugue. His inspiration here is said to have been

the Classical Roman baths with their rooms on three scales.

Finally,

as to the shapes of individual rooms, he offers up a smorgasbord of possibilities,

from the square and the circle to rectangles in a variety of ratios of

width to length.

The

ratios of width to length -- both as published in his Four Books of

Architecture and as measured in the completed villas themselves --

have been the subject of a great deal of recent scholarly research with

little concrete result.

Rudolph

Wittkower in 1949 published Architectural Principles in the Age of

Humanism with his breathtaking proposition that the ratios of width

to length in Palladio's rooms are based on the harmonic proportions of

music. In other words, that Palladio worked on an "If it sounds good,

it'll look and feel good" principle. The enthusiastic acceptance of this

theory was only modestly tempered by the fact that some of Palladio's

rooms reflect harmonic musical proportions and some don't.

But

Wittkower was right in emphasizing the importance of number theory or

numerology as a foundation for Palladio's proportions. Harmonic proportion

provides an insight to some of Palladio's villas, particularly the later

ones, but equally or more important was the theory of "perfect numbers."

The numbers "6" and "10" were deemed to be "perfect" numbers because they

reflect the proportions of the human body in several dimensions, including

the ratio of front-to-back and side-to-side. In other words, you would

feel comfortable in a room that was in the ratio of 6-to-10 because the

room would have the same proportions as your own body. Then, in a grammatical

challenge, the number "16" was deemed to be the "most perfect" number,

primarily because it was the sum of the other two.

The

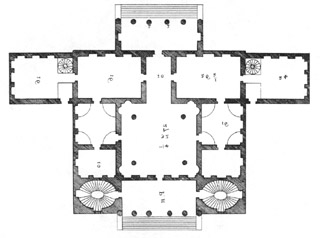

Perfect Scale of Villa Cornaro

Now

let's put all this together in an analysis of the central core of the

villa I know best, Villa Cornaro. In 1570 Palladio published the floor

plan as part of Plate 36, Book II, of his Four Books of Architecture.

The

first thing that strikes us is that the central core is one of Palladio's

preferred shapes, a square. Next we notice the fugal variation of room

sizes. You can't see it, of course, in Palladio's floor plan and elevation,

but the heights of the rooms modulate as well.

Then

let's look at the proportions of one of the long rectangular rooms on

the north. Now we are moving toward the central inspiration of Villa Cornaro.

The ratio of length to width in the room is 3-to-5. But consider 3-to-5!

That's the same as 6-to-10. Yes, this room is in the ratio of the two

"perfect" numbers. You'll feel very comfortable in this room. And the

actual width of this room? Sixteen Vicentine feet: the most perfect number

of all.

So

here you are looking at Palladio's perfect room. A remarkable artefact

to be sure, but remember Palladio's fundamental premise: the parts must

relate to the whole and to each other. How does that work here? Well,

obviously, there is another room the same size on the north. But then

on both the east and west sides, there is a square room with a small room

behind it. Those two rooms together repeat the dimensions of the perfect

rooms on the north! Now that only leaves the large room. The relation

here is not obvious, but it finally emerges. Yes, the grand salon is two

of our "perfect" rooms side by side.

There

you have the secret to the harmony and balance of Villa Cornaro: the central

living area is six repetitions of the module of the perfect room, all

set within a square.

The

Living Villas

But

harmony and balance, like some of the finest wines, don't travel. You

can transport the double projecting portico of Villa Cornaro to Drayton

Hall or the Miles Brewton House in Charleston, to Shirley Plantation in

Virginia, to a pleasant home on Woodward Way in Atlanta, to thousands

of other homes across America. And, lord knows, you can always transport

wood or other even cheaper materials. You can transfer the 5-part profile

of Villa Barbaro, the occuli of Villa Poiana, or the encircling arms of

Villa Badoer. But the balance and harmony -- the balance and the harmony

that are the core of Palladio -- don't travel. They can be found only

in the Veneto.

They

don't travel, but they never age. Unfazed, unaffected by any pale imitations

-- the villas live vibrantly today.

.

. . As vibrant today as in the crisp, cool mornings

when Palladio walked there.